In a time that honored martial prowess and piety above all else, the warrior bishop was the physical embodiment of the medieval ethos: a soldier of Christ — miles christi. When Christian and heathen worlds collided throughout Western history, religious differences often led to physical confrontation. In comes warrior bishops.

This controversial fusion of clergyman and soldier played a pivotal role on the medieval battlefield and shaped the West’s understanding of piety, violence, and warfare. The warrior bishop became a symbol of Christendom’s struggle against forces and ideologies that threatened its existence.

So where did they come from, and why were they a vital part of medieval history?

To understand how these unique figures shaped the medieval Church’s perception of conflict, let’s examine their development throughout the medieval period. We will examine four distinct periods: the Late Roman Era, where bishops would first lead soldiers and fight out of necessity; the early middle ages, where a consolidation occurred between Church and state leading to a militarization of the priesthood; the Crusades, where heroes and villains would arise among the clergy; finally we’ll look at the Late Middle Ages, where brazen overreach would lead to the Church’s rupture.

Reminder: You can support us in forming minds and rebuilding the West by unlocking our members-only content:

✔️ Full premium articles every Tuesday + Free content Thursdays

✔️ The entire archive of content: Western history, literature, and culture

✔️ The Great Books lists (Hundreds of titles that influenced Western thought)

Join to start reading and support the mission today 👇

Power Shift: Bishops on the Battlefield in the Late Roman Era

Despite widespread oppression throughout the Roman Empire, early Christians maintained a pacifist philosophy. Persecution and martyrdom were ever-present dangers, often borne with meek acquiescence in true Christ-like fashion. Having little political power, Christians were left to the whims of those with more earthly authority. This power dynamic shifted, aptly, on a battlefield – Constantine’s vision before the Battle of Milvian Bridge in 312 A.D. signaled a momentous change in Christianity’s fate. Not only would it be the impetus to change Christianity’s official status as a religion, the battle where Constantine commanded his men to paint a Chi Rho on their shields was a precursor to more direct Christian involvement on battlefields of the future.

Constantine would consequently be the first to introduce clergymen directly onto the front lines. Accompanied by symbols of the cross flying high over Roman legions [1], clergymen joined soldiers during battle – not as fighters, but as symbolic additions meant to boost morale. Though priests now accompanied troops during military campaigns, their role changed little from their peacetime brethren. Offering mass, hearing confession, and tending the sick were all standard duties of these wartime clerics [2].

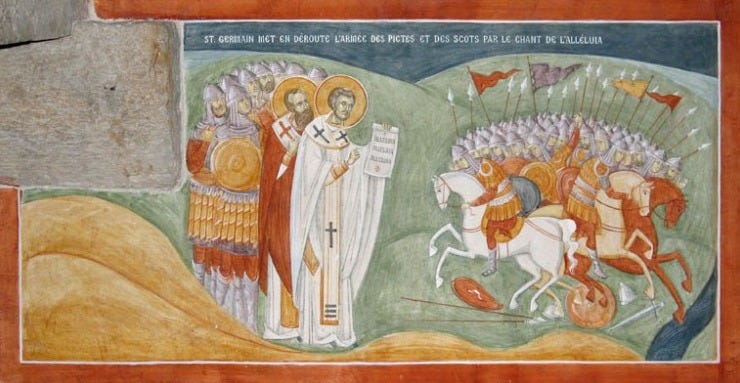

Bishops weren’t seen exercising full military command until nearly a century later. One of the first examples took place shortly after Easter in 429 when Germanus, bishop and former duke of Autissiodorum, assumed leadership of the Britons during a Saxon raid on Mold, a small mountain village in northern Wales. The bishop’s prior experience as general surely proved invaluable when he hand-selected a group of soldiers, carried their banner, and led the force to a vale, hoping to ambush the invaders before they reached the village. As the raiders approached, the freshly baptized Britons gave three shouts of “Alleluia!” – their new battle cry taught to them by Germanus. Startled by the yells reverberating throughout the low hills, the raiders assumed the sound could only have been made by a massive army, fleeing before any blood could be spilled [3]. Germanus’s fellow bishops were elated that he had won the battle without bloodshed, calling it a “victory gained by faith and not by force.” [4]

Germanus would develop a reputation for his confrontational style. The bold bishop famously challenged the barbarian king “Goar,” ruler of the Alans, convincing the king to hold off an attack against insurgents in Armorica while waiting for direct orders from the emperor in Italy (the Alans were sent to quell the rebellion by Aetus, the most influential general in the empire at the time). To defy a king was no small feat, and soon Germanus had a cult following. His heroic exploits were eventually passed down across generations and his name became etched into legend – he was a shoo-in for sainthood.

The Church at the time was not so enthusiastic about the confrontational style that Germanus and bishops like him championed. St. Paul’s warning that “We wrestle not against flesh and blood but…against spiritual wickedness in high places” [5] seemed to refute the necessity of having clergy lead armies of soldiers. That a cleric should be engaged in spiritual, not physical, combat was the prevailing viewpoint. Presented with this tension, the early Church wrestled with properly defining clergy’s role during wartime. The first full-fledged clerical prohibition on military service appeared at the Council of Chalcedon in 451:

“We decree that those who have once joined the ranks of the clergy or have become monks are not to depart on military service or for secular office. Those who dare do this, and do not repent and return to what, in God, they previously chose, are to be anathematised.” [3]

Later in 546, Canon I of the Council of Lérida specified that clergy were forbidden from spilling blood:

“…It is established that those who serve at the altar and handle the body and the blood of Christ, or who are allotted to the office of the holy vessel, should restrain themselves from all human blood, indeed [even] from that of the enemy…” [3]

The Church teaching was clear: clerics should not engage in military service and should not spill blood. Despite these official restrictions, the days of finding a bishop at the head of an army had just begun; bishops continued to participate in military ventures over the next millennia, becoming trusted advisors, generals, and, in some cases like Germanus, military heroes.

Thus a new kind of leader had emerged from the vestiges of the dying western Roman Empire – a shepherd of Christ who not only led believers in spiritual matters, but also commanded armor-clad warriors to protect his flock from flesh-and-blood dangers.