Future wars won’t just be fought between nations — they’ll be fought between entire civilizations.

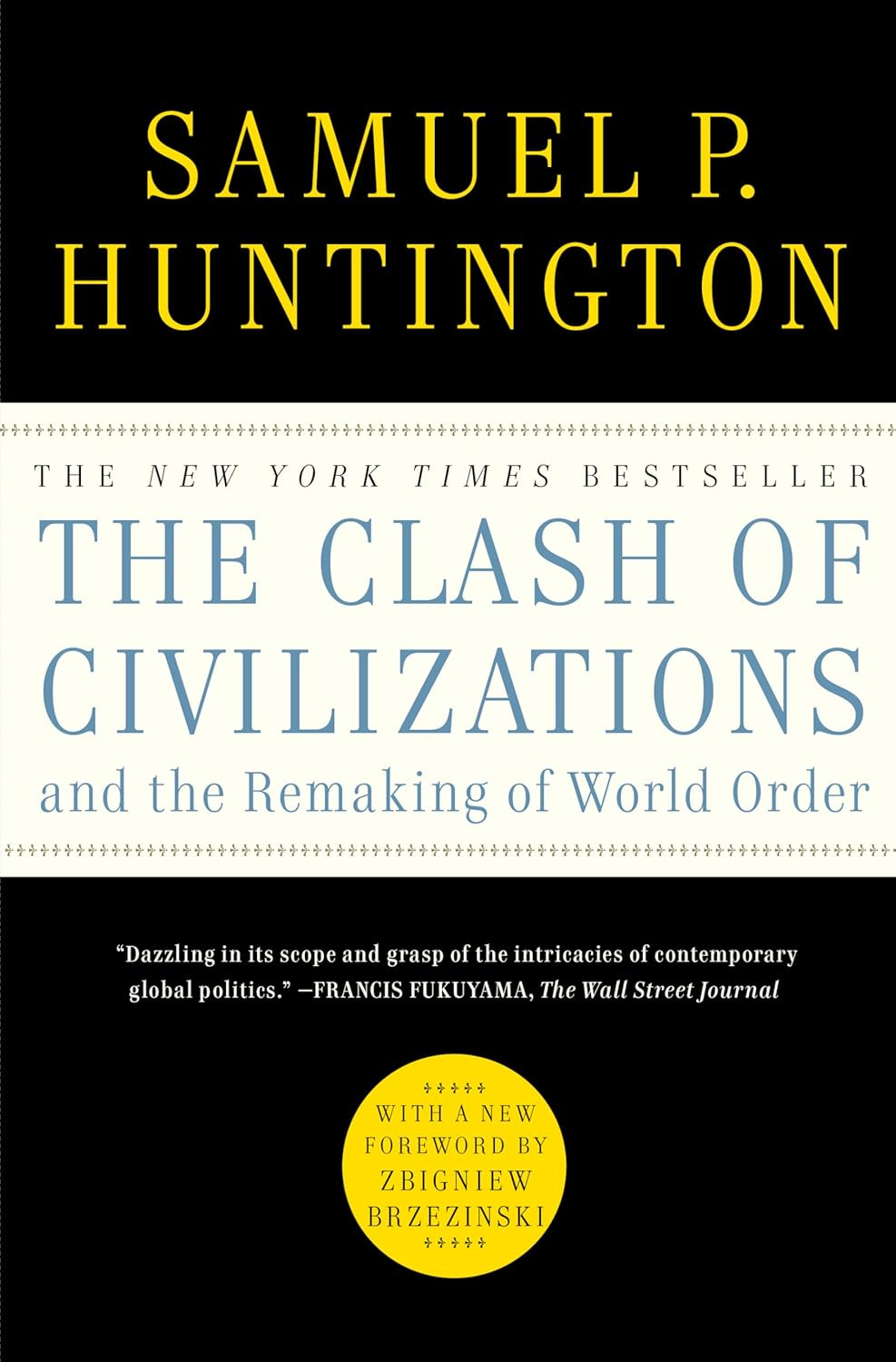

That is, according to political scientist Samuel P. Huntington and his controversial thesis presented in The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (1996). Huntington’s argument challenged the dominant post-Cold War assumption that ideological or economic rivalries, like capitalism versus communism, would continue to define global politics.

Instead, he claimed that the defining fault lines of the 21st century would be cultural and ultimately civilizational with religion as the key differentiator.

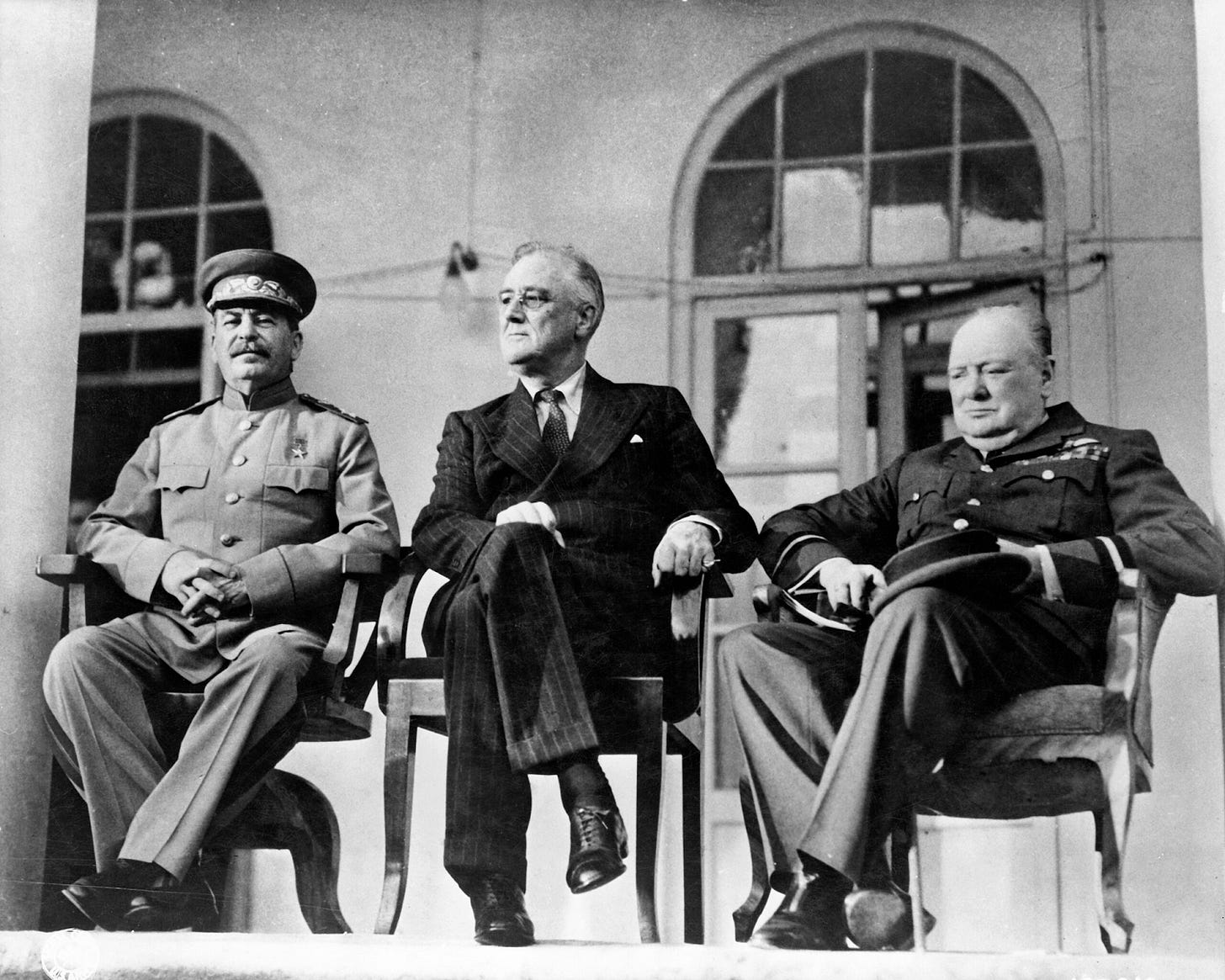

Already during the Cold War, the world teetered on the edge of nuclear war between the capitalist West and communist East. At face value, this conflict appeared to be ideological: market-driven democracies opposing centrally planned authoritarian regimes. But looking deeper, the blocs were rooted in in fundamentally different civilizations.

The U.S. led a Western civilization grounded in individualism, secularism, and Protestant-Catholic ethics. The Soviet Union, meanwhile, while communist in theory, was shaped by centuries of Eastern Orthodox tradition and a collectivist ethos distinct from the West. Beneath the politics was a deeper divide in worldview, identity, and cultural memory.

While the West “won” the Cold War, Huntington warned that the age of civilizational warfare was just beginning.

Reminder: You can support us in forming minds and rebuilding the West by unlocking our members-only content:

✔️ Full premium articles every Tuesday + Free content Thursdays

✔️ The entire archive: Western history, literature, and culture

✔️ The Great Books lists (Hundreds of titles that influenced Western thought)

Join to start reading and support the mission today 👇

Huntington’s Civilizations

In his framework, Huntington identified a handful of major civilizations that shape global affairs.

The leading world power has been Western Civilization at least as far back as the late Medieval period. Western Civilization now includes the U.S., Canada, Western and Central Europe, and Australia. Whether to include Latin and South America as part of the “West” is an ongoing debate, as these generally exhibit a unique blend of Catholicism, indigenous cultures, and post-colonial development. Overall, the West historically owes its character to Catholic and Protestant Christianity, liberal political traditions, and capitalist economies.

Sharing a common root with Western Civilization in the Roman Empire, the Orthodox Civilization consists largely of Russia (emerging from the Byzantines) and other former Soviet states with Eastern Orthodox roots. Though once part of a communist bloc, these nations retain a distinct cultural and religious identity.

A third civilization is the Islamic Civilization, spanning North Africa, the Middle East, and parts of South and Central Asia. This bloc is united by the Islamic faith, though deeply divided internally between sects and ethnicities. Iran, Pakistan and Egypt are some leading powers from this civilization.

Dominated by China, a fourth civilization is called the Sinic Civilization. This civilization primarily includes areas influenced by Confucian culture, such as Korea and Vietnam. Huntington saw this bloc as distinct for its emphasis on hierarchy, social harmony, and collective order.

A fifth civilization is that of the Hindus. Centered in India and Nepal, this civilization reflects the complex traditions, spiritual beliefs, and historical experiences of the Indian subcontinent, especially those elements distinct from British colonialism that infused Western elements into their culture.

Further eastward, the Buddhist Civilization includes nations like Thailand, Myanmar, and Cambodia, influenced by Theravada and Mahayana Buddhist traditions.

Huntington also believes Sub-Saharan Africa may constitute another distinct civilization in the making. This would include nations like Ghana, Ivory Coast, and Liberia.

Other nations — such as Japan, Israel, Ukraine, Turkey, and South Africa — he classifies as "cleft" nations, whose cultural identity sits at the intersection of larger civilizations or is internally divided due to historical or political circumstances. These nations stand apart or in transition between other civilizations and in several instances are already revealing themselves to be flashpoints in the clash of civilizations.

But it’s why these civilizations will clash that is the key to understanding Huntington’s theories of civilization warfare.

Why Civilizations Will Clash

To be clear, Huntington was not endorsing or encouraging war, but instead offering up his observations on the trajectory of world conflict, writing:

“This is not to advocate the desirability of conflicts between civilizations. It is to set forth a descriptive hypothesis as to what the future may be like.”

Huntington lays out several reasons why these civilizations are, and will continue to be, at odds:

Civilizational identities are enduring. History, language, culture, tradition, and religion run far deeper than political ideologies and are too fundamental to each civilization to dissipate into a single world civilization any time soon. While nations can change governments or adopt new economic systems, core identities are remarkably resilient and will persist for a long time.

Globalization increases contact and friction. With world populations growing and the interconnectivity brought by high speed travel and communications, the world is becoming smaller. Interactions between civilizations are increasing, intensifying the consciousness of differences between civilizations and provoking conflicts.

Religious identity is on the rise. Local identities have faded in the modern world, leaving only religious identity that transcends national boundaries and unifies a civilization. The end result? Civilizations are made stronger.

The dominance of the West is resented. The West is still the supreme power, but that standing power has ignited a desire among the non-West to return to their own civilizational roots and avoid the West’s influence. The West defends its hegemony and confronts threats that double-down on their own non-Western ways of influencing the world.

Culture is stickier than politics. Our cultural identities are less changeable than political and economic characteristics, meaning we can give up our nation or style of commerce long before we will give up our religion.

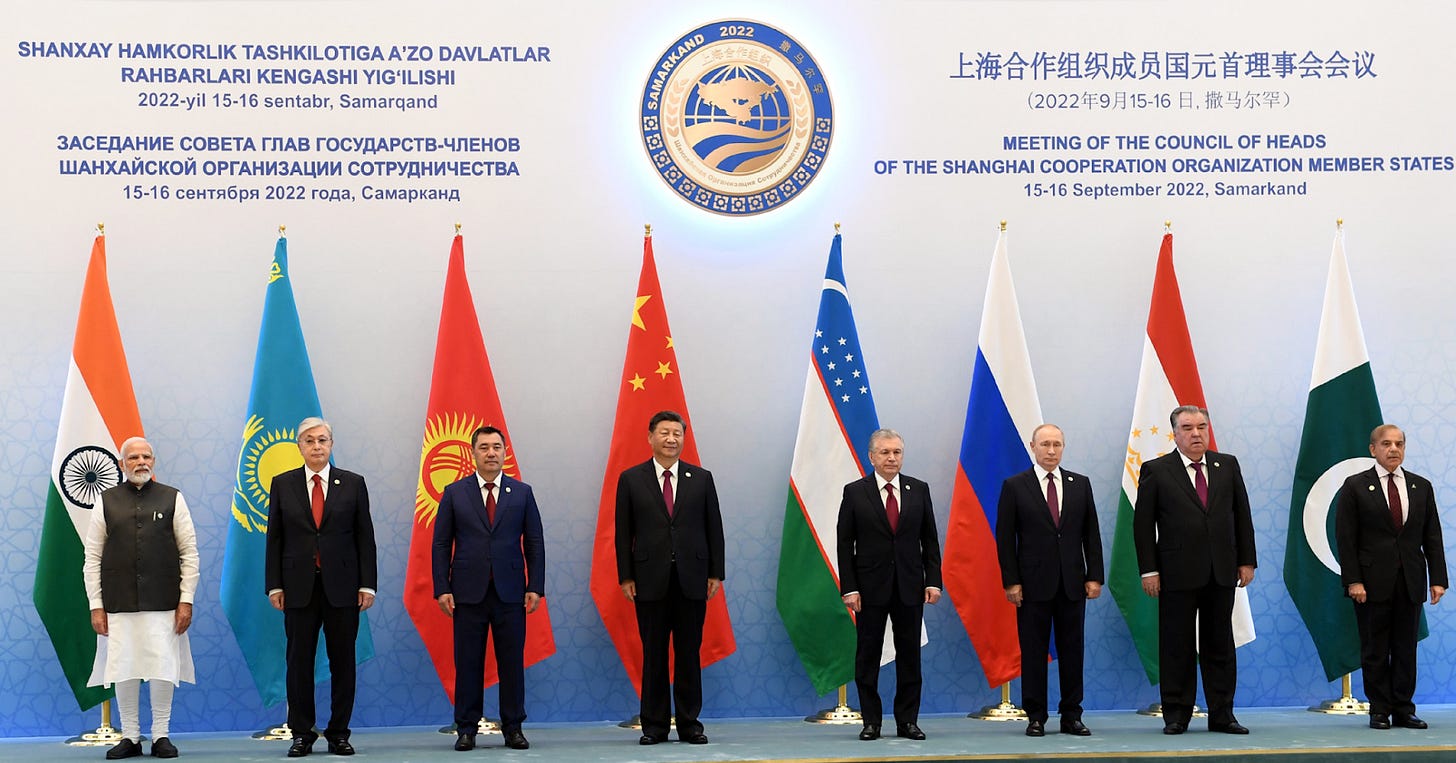

Regional cooperation reinforces civilizational blocks. Groups like the EU, ASEAN, and BRICS demonstrate how economic cooperation often aligns along civilizational lines, deepening cultural alliances. This “economic regionalism” enhances civilizational identity and consciousness, increasing the likelihood that conflicts between nations will be replaced with conflicts between civilizations.

These reasons explain why the core of modern geopolitics revolves around the West’s clashes with the other world civilizations, what has been described as the clash between “the West and the Rest”.

The West vs. The Rest

Clash of Civilizations describes how the world is entering a new phase of world politics in which Westerners no longer dominate the globe alone, but must operate with other non-Western cultures in a multi-polar world.

But as the unipolar moment of Western dominance fades, other civilizations face a choice in dealing with the West. Huntington outlined three strategic responses.

First, Non-Western nations can pursue independence (or perhaps isolation) from global affairs, and with it, the global economy. North Korea is a prime example. These nations typically refrain from treaties, agreements, and economic trade with the West, often facing Western sanctions for actions deemed out of line by the West.

Second, non-Western countries could jump on the West’s bandwagon, adopting Western values and governments to become allies of the West. Post-war Japan, though now called a “cleft” nation by Huntington, has followed this trajectory post-WWII.

Or, lastly, non-Western powers can attempt the complex strategy of uniting, modernizing, and ultimately competing against the Western system. BRICS is a perfect example of this collectivization of the “Rest” against the West, leading to a truly multipolar world order.

It’s this last strategy that the West has feared the most, and it’s happening — slowly but surely.

And the Wars Begin

Nearly 30 years after Huntington’s book, many of his forecasts are coming true.

For decades the West has been at war with various parts of the Islamic civilization — through numerous conflicts in the Middle East, the global War on Terror kicked off by 9/11, and now the West’s direct involvement against Iran.

While wars in the Middle East have become a staple of modern history, few would’ve believed another war between European powers would be seen again.The Russia-Ukraine war marks a direct clash between Russia, a resurgent Orthodox power, and Ukraine backed by NATO, the military alliance of the Western world.

Even the nuclear-armed Hindu and Islamic worlds have come to blows recently in the brief conflicts between India and Pakistan. While not full-scale war, their skirmishes and political hostility remain a flashpoint.

But the mother of all civilizational clashes will be the conflicts between the West and the Sinic world. The U.S.-China competition spans trade, technology, influence, and ideology. The clash between the Sinic and Western civilizations is a classic case of Thucydides trap: the fear of a rising China displacing a dominant U.S. leads to rising tensions and the potential for war.

But the competition over Taiwan promises to be the real flashpoint in a hot war between the West and China — what everyone believes will be the real kickoff to the next global war.

A New World

The world is no longer a simple battleground between capitalism vs. communism, or democracy vs. autocracy. Instead, what we face is a more primal contest between older, deeper civilizational identities.

What Huntington predicted as a “clash” may not be a singular world war, but a pattern of ongoing tension, competition, and intermittent violence — played out at the level of civilizations.

Whether over ideology, resources, territory, or influence, these conflicts are increasingly rooted in incompatible visions of life, humanity, and theology. The world, Huntington warned, is not converging into one civilization — but dividing more clearly into many. So much for fears of a one world government.

Nonetheless, the clash of civilizations between the West and the Muslim, Sinic, and Orthodox worlds is already underway as described by Huntington, and a new civilizational order is poised to emerge, one where the West may not rule supreme anymore.

For those interested in reading more on Huntington’s ideas, check out his book The Clash of Civilizations.

Frankly speaking, I don’t buy into Huntington’s theory so much mainly for one reason: different civilizations are not born to fight each other.

Actually, every civilisation contains aggressive/radical sects and peaceful/centrist sects, more or less. What matters is not only cultural differences, but also how those differences reacted to political conditions, and what makes one side prevail and other sides lose. It’s more about how civilisations evolve in the global and local stage, rather than how their fixed traits lead to destruction.

To say chimpanzees are different from humans is easy but unhelpful. Maybe we can do (and I am doing) something new based on those differences?

Have been thinking much the same myself. I think the US is already engaged in such a civil war. Shots have been fired. People keep talking about secession. People in rural Oregon are talking about joining Idaho. People in rural California are talking about separating from the Bay Area and Los Angeles and forming a new state. There’s talk about a coming civil war. I think we’re in one.